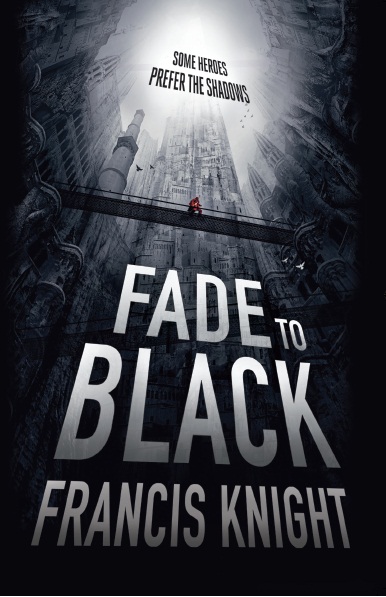

Fade to Black - Francis Knight (#1 Rojan Dizon Trilogy)

It was interesting to approach this book so

soon after reading another book, by another Frances, looking at overtly similar

themes in the world building. Frances Hardinge's A Face Like Glass also

features a vertical society, which neatly maps onto a Marxist view of societal

change. In Francis Knight’s Mahala, just like Hardinge’s Caverna, the lower

classes live physically at the bottom of the heap, and upper classes are living

it large in the upper echelons of the city. While the cities couldn't be more

different in content, in terms of political impact they couldn’t be more

similar.

While Hardinge’s wonderful novel focusses on a

young protagonist, and explicitly uses the proletariat uprising as a plot

theme, Knight’s focusses on the underclass fighting back on a much more

personal level. Rojan Dizon is a pain-mage, and bounty hunter, much in the mold

of the Harry Dresden school of character: a lovable rogue, embedded in the

underbelly of his city. Instead of an alt-Chicago, our urban playground of

choice in Fade to Black is Mahala, a ‘vertical’

city rising out of a valley. Technology is proto-steampunk; the gun has just

been invented, a pseudo-petrol, 'Synth', has just been outlawed due to its

deadly effect, transport involves ‘carriages’ and a cages on wires in the style

of cable-cars.

The premise of this worldbuilding sounds

original, and, were it as fully realised as Hardinge’s vertical city it could

possibly have been a truly unique and memorable fantastic experience. Instead,

we are treated to a world that sounds

cool on paper, but is never fully realised. Throughout the book, we are treated

to what seemed to be unrealistic and not-fully-realised locations and moments.

Futhermore, the central premise of the world building, Mahala’s very

verticality, is effectively negated from chapter three onward.

Most of the action takes place in the ‘Armpit’

(colloquially, and uninspiringly known as the ’Pit), the very bottom of the

city which has been sealed off since the discovery that ‘Synth’, the major

power source in the world, was toxic. On entry to the ’Pit, we see that despite

the lingering threat of the ‘Synthtox’, life is actually pretty hunky dory:

As

we descended, I could hear the life of the city. Music! I hadn't heard any real

music in years: the Ministry disapproved, considering most lyrics to be

seditious ... Here, songs blared constantly from broken windows, the

old-fashioned music that had had a brief resurgence just before the 'Pit was

sealed, all heavy throbbing beats and wailing words, a desperate outpouring of

anger against the synth. [pg.73]

On top of music, they have freedom of worship

of the major deity, meat,

Coliseum-inspired games arena and are generally pretty free and happy compared to Upside. Well, as best

as I could tell in some parts of the novel. And then there are other parts

were, without telling us why or how Knight suddenly realises that Downside is in fact this shitty place, as we are

constantly reminded by the rather info-heavy first-person narrative of Rojan

himself. However, apart from being as downtrodden as the Upsiders, and yes,

having the threat of Synthtox heaped on them, there doesn’t seem anything that

makes the Pit and worse than Upside.

This is not the only example of poor

plot-building, which remains either entirely too predictable or, on very rare

occasions, is presumed known without actually informing the reader. I found

myself all too often, as early as chapter three predicting almost the entire

concept and premise of the book, the actions and reactions of characters. When

there is a side plot it is both

entirely artificial and entirely predictable as it is possible to be, even to

the point where it is acknowledged as such by the characters of the book.

For example, on looking for the niece of the

main character, Rojan uses his pain-magic (magic that is powered either by

one’s own, or others’, pain. Rojan is far too moralistic to use the latter, of

course. The major adversary is as obvious as can be just by that description.)

to pinpoint her location: EXACTLY west of a companion character’s house. Obviously Rojan is

naturally able to pinpoint true North by instinct, even under the city, so

finding true west of the house is easy. Eventually, after a pointless cage trip

to exactly above Pasha's house, we find that the niece is being kept in the

keep of the cod-medieval castle under the city. To this mighty news, we hear:

'No surprise, we thought as much. We've just never known for sure, and not

enough help to just go for it, no one to tell us where in the keep'

[p.181]. Oh, hooray. I've wasted 50 pages finding the niece only to be told you

already knew where she was?

One of the most

jarring elements of the novel as it continues is the sense that Rojan as a

character never seems to have a grip on just how terrible the events he is

witnessing, and attempting to forestall are. Trying to avoid spoilers, suffice

to say many innocent parties are in terrible danger, and are, in often gruesome

ways, tortured or threatened so. I found it very odd, and at no point is this

well explained, that all those in danger are women, particularly young girls,

and while the author is female this cannot be seen as an excuse for what can all-too-easily be read as a misogynistic sexualisation

of the magic system. The main character, buried in a worldview where women are

there to be used, and thrown aside, who proudly acknowledges in a scene where

three women discover they are all being played by him early on in the novel

that a two week relationship is a long one, obviously doesn’t notice this. We,

as readers, must, and it’s a difficult concept to take with lack of explanation

attached. Further, throughout the narration is just so cheerful, so off hand

and off beat. At times this comes across really well, particularly in the

in-between segments between plot points, or where we are being (not often

enough) dipped into the world of Mahala, but when it comes to descriptions of

the horrors Rojan is facing, he’s far too nonchalant to be believable.

This simple and

entirely-too-convenient plot comes to a head following a couple of hundred

pages filled with love-triangle, angst, violence-occurring and

all-too-obvious-side-quests with the most horrific of endings. It’s so obvious,

so singularly uninspiring that it has been the subject of parodies since before

its most famous instance in the 1970s. I found myself wishing that it wasn’t going to

happen in the way it did, and then physically having to prevent myself from

hurting the poor book when it eventually happened.

Finally, affixed to this is prose that is more

a violent shade of violet in places than merely purple. There are sentences

that literally don't make sense. Take this, from the very first page: 'One

sight of me, a burly man in a subtly armoured, close fitting all over with a

flapping black coat, and the and the scavenge-rat teens that call this place

home took to their heels'. We later find out that an 'allover' is some kind of

garment, but the combination of tell-not-show and spelling mistake makes for a

reviewer who has to reread that sentence ten times trying to work out what it

means, before moving on. Elsewhere we sentences that mix action and description

to disastrous results: 'Chains rattled and clanked overhead, cages whizzed by,

sometimes too close for comfort so I ducked instinctively' [p. 123], or the

splendid paragraphs at the start of chapter eleven:

By

the time the cage set us down on firm ground, I was ready to kiss the street ..

I might even have done it, if the stink of the place hadn't warned me. It

smelled like shit. Literally.

My

stomach roiled over. It hadn't recovered from the cage yet, and now I was being

assaulted by a smell strong enough to make my eyes water. No wonder the street

was empty. [p. 183]

Yes. We know that it smells already. From the

paragraph before.

Furthermore, the method the plot uses to go

forward often consists of rhetorical questions: 'Those old warehouses were

pretty small. You could probably fit half a dozen into one of the minor new

ones up there in Trade. The bigger, newer ones took up vast cubed acres. So

where else? And more importantly, where was he moving them from?' [pp.

174-5] And the occasional info-dump, like the entirety of chapter three. All

told, points we can possibly forgive

individually from a debut author, but not collectively.

My concluding thought was as a result of all

this simplicity was that if the derivative simplistic nature of the book was

substituted into a less-horrific setting we could possibly have some

average-to-good middle-grade YA. As it is, we have a box of cheap, predictable

tricks and a horrible sense that this was an idea that had some real potential

to it, and was cruelly taken over by a Pixar movie whose plot it apes, if said

movie were placed in a gritty, over-noired fantasy setting.